Borne Sulinowo

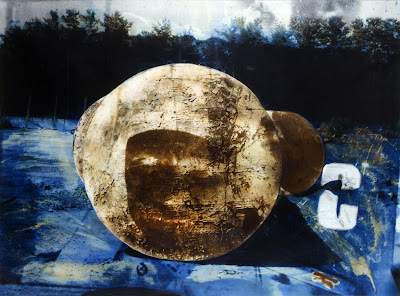

Slide, silver gelatin print, toners, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 67cms x 111cms, 1995

While most of Sloan's work is firmly rooted in Northern Ireland Northern Ireland

In 1993 and 1994, as part of a project organised by Wladyslaw Kazmierczak, Sloan visited the town of Borne Sulinowo Poland

Untitled, Borne Sulinowo, cibachrome print, 29.5cms x 19.5cms 1995

Untitled, Borne Sulinowo, cibachrome print, 29.5cms x 19.5cms 1995

Untitled, Borne Sulinowo, cibachrome print, 19.5cms x 29.5cms, 1995

The deserted Borne Sulinowo is a striking example of a problematic social space, like the other environments Sloan has sought out. While there is no overt connection with the North, Sloan's work acts as a quizzical commentary on the role of the British Army in Northern Ireland Northern Ireland Northern Ireland

In the Borne Sulinowo work he is, paradoxically, trying to resurrect what has been lost only to confirm its loss. "They're images that have been destroyed, and I've taken them and destroyed them again." It's an exercise in mixed feelings, but there is little that is positive in his bleak view of what comes across, finally, as a pointless exercise in the perpetuation of human misery. It's tempting to see the residual images of the Soviet troops, literally superimposed in many cases, on the Polish background, as victims, as individuals caught up in a context they mistakenly believe is in their best interests.

Extract from A Broken Surface: Victor Sloan's Photographic Work by Aidan Dunne in Victor Sloan: Selected Works 1980-2000, published by Ormeau Baths Gallery and Orchard Gallery, January, 2001.

The work comes from two visits he made to the Polish town of Borne Sulinowo

Amongst the flotsam and jetsam, Victor Sloan found a number of photographic images, mostly of Russian soldiers, which had been defaced by angry and bitter locals. The connection with his own work was obvious, and Sloan was further struck by the similarity in the lives of the Polish and Irish peoples, saying that Poles like us, had ‘lived their sufferings’.

Untitled, Borne Sulinowo, cibachrome print, 29.5cms x 10 cms, 1995

Untitled, Borne Sulinowo, cibachrome print, 10 cms x 29.5 cms, 1995

Untitled, Borne Sulinowo, cibachrome print, 29.5cms x 19.5cms, 1995

The result is this series of photographic works, found photographs re-photographed and treated with colour, and abstract markings which highlight the ravages of the vengeful Polish people.

Leader, silver gelatin print, toners, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 111cms x 80.5cms, 1995

The top half of Gorbachev’s face has been torn away, but Sloan has wittily beautified the photograph, by tinting his lips pink, just as the Russians have always done to idealise images of their leaders. A soldier receives the same treatment, his battered face given the same lips, along with baby-blue eyes and blond hair. Touching up the photographs in this way has the effect of exaggerating the original vandalism. In another piece, a young soldier has his face obscured by a superimposed photograph of some of the ammunition he and his comrades left behind.

Cemetery, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 80cms x 111cms, 1995

Sloan makes reference to other aspects of Poland

Helicopter, silver gelatin print, toners, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 76cms x 111cms, 1995

While Sloan was working on this series, the ceasefires here were announced. This clearly gives the work a significance beyond the original intention and, while direct comparisons are rarely useful, the underlying optimism of Sloan’s images must strike a chord with anyone living in the north of Ireland

Extract from Scratching at the Surface by Colin Darke, Derry Journal , Northern Ireland 14th Februar y 1995

Statue, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache,111cms x 80cms, 1995

Containers, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 80cms x 111cms, 1995

Bars, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 80cms x 111cms, 1995

“…sail at last out of the bad dream of your past.”

Seamus Heaney,

The Cure at Troy

I

The German playwright Heiner Müller once remarked: “Gorbachev has ended the Cold War by dissolving the East/West conflict, the rivalry of ideologies in the North/South conflict. It is no longer a question of ideas but of realities. Thus, he has reduced the struggle between capitalism and socialism to the core itself: the antagonism between poor and rich. This antagonism is now getting universal significance, and full force.”(1) Muller also spoke of the rift between East and West Rome, Rome and Byzantium, which is dividing Europe in irregular curves, and which can be seen in a flash, when, after the loss of a binding religion or ideology, the tribal fires are being newly lit. A rift into which, for example, Poland

Where is

Helmet, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 80cms x 111cms, 1995

II

During a reading at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Berlin

If you are not a ‘seer’, but make extremely good use of your eyes, one could speak of a craftsmanship of seeing. While such a craftsmanship was not unusual in former times, today we have to face an undertaking which is producing perceptible phenomena. This could be the form a threatening industrialisation of seeing might take.

What in fact is the real tree? The one which you perceive if you stop, and which you can distinguish a branch from a leaf, or the one you perceive while it is passing the car’s windscreen, or the peculiar screen of the television? From the answers to these seemingly stupid questions, practical consequences, the everyday life appears. If photography, as understood by its pioneers Niepce or Daguerre, no longer exists but is only a stop in the image, and if stills are therefore merely “stations” on the way of the sequences passing the eye, we can expect a passionate turn to the view, to which the other view characterising the craftsmanship of the amateur photographer will soon fall victim, because the industry of seeing will be to the fore. This industry will owe everything to the motor, the transmitter and receiver of the “waves”, which hence-forth transmit the video signal as well as the wireless signal. We are facing an excessive breaking-in of the eye and the danger of a subliminal “optically correct” conformity, which would accomplish the conformity in language and writing.(4) In consequence of the mechanization of sensuality you don’t have to see any longer. This is what Walter Benjamin meant when he wrote that taking touristic photographs is erasing memory. And, not to remember means to be unable to know anything by experience any longer.

Wall, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 80cms x 111cms, 1995

III

In the summers of 1993 and 1994, Irish artists (among them Victor Sloan) at the invitation of Wladyslaw Kazmierczak, director of the Baltic Art Gallery Ustka , Poland

Borne Sulinowo had been a secret base of the Soviet Army; a town with 25,000 inhabitants which was hidden in woodland close to the German border. The red Army left the base overnight in the winter of 1992. Since then the town has lain deserted. In the ghost town, in which the Soviet street names have been changed (e.g. to ‘Street of the Polish Army’), now only a police station exists, as well as a tiny bar with three or four tables, a TV set and a wall hanging depicting the Polish national colours. The landscape to be seen on the journey from Ustka to Borne Sulinowo resembles the landscape of the Irish Midlands. Flora and Fauna are quite amazing. The story goes that, due to financial difficulties in the mid-eighties, the Polish farmers could not afford to buy fertilizers, and much of the land remained untilled. The effect was that nature took over again quite fast. Wild flowers blossomed; storks came back, wild boars, foxes and herds of deer roamed free.

The first impression of Borne Sulinowo is that of a ‘green’ town; an idyll. But in fact it is not. Like all other places from which the Soviet Forces (or in

For the Polish people, Borne Sulinowo symbolizes the former military occupation of their country by Soviet troops. But were the soldiers, who had been stationed there, living as victors? No, they were not. It is depressing to walk through this town, where all doors stand open. From the state of the slightly differing flats in the housing blocks, you can tell who lived there. The lower the ranks the poorer had been the facilities provided. In many of the huge dormitories the walls are completely damp and mouldy, and they must have been like this even while Soviet soldiers lived there. In some of the flats you can still find the food on kitchen tables, as if the inhabitants had left in a hurry. Even the officers’ mess has gone to ruin; the parquet floor of its dance hall resembles a switchback, and in the heating power station, one wonders if the ovens, not quite repaired by using lumps of clay, ever worked at all.

In this environment, fragments of faded propaganda poster, on which the Social Realist artists, “the engineers of the human soul” (Stalin), presented the ordinary person in a context of utopia, strike one now as surreal.

Wire, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 80cms x 111cms, 1995

IV

Previously, Victor Sloan produced photographic works which dealt with his own personal history, in the context of a particular Northern Ireland Orange Derry as a visual emblem of a divided city).(5)

Victor Sloan, like the other Irish artists, who went to Borne Sulinowo (Brian Connolly, Sean Taylor), was inspired by his experience there to make a new series of images. On first sight, it is a visual narrative about the after effects of the withdrawal of the Soviet Army from

The Canadian artist Jeff Wall has dealt with the death of the Red Army in his large-scale cibachrome image titled “Dead troops talk”.(6) Jeff Wall reconstructs a subtle counter-tale to the tale that Late-Capitalism wishes to tell, and so stridently asserts. At this point in the historical drama, the Soviet Zombies take up their full phantasmagorical presence, as both spectres and spectators of Late-Capitalism. Wall reinterprets, repositions, the narrative set up by Late-Capitalism that, of its own triumph, as being a rhetoric of bombast.”(7)

In his new series Victor Sloan takes us through a minefield cordoned off by barbed wire. We see a military map of

Ammunition, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 80cms x 111cms, 1995

Walter Benjamin made it clear in his essay “Work Of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” that, for him, the camera is an instrument that enlarges vision. He likens the camera, for example, to the surgeon’s knife that can operate dispassionately on the human body, and so, by seeing it in fragments, can enter more deeply into its reality. Sloan distrusts such certainties about the camera and camera-captured appearances. The camera’s objectivity is illusive, the neutrality delusive. Victors Sloan’s knife is the brush, the sponge, the pin or the blade, at work in his ‘documentary’ photographs. Sloan’s works - to site a phrase André Breton used to describe Max Ernst’s over paintings – are built on the grounds constituted by “the readymade images of objects”. The deferred action or Nachträglichkeit, or aprés-coup, is importantly a function of the readymade, which lying at hand, becomes the vehicle for a past experience - one that has made no sense at the time it occurred – to rise up on the horizon of the subject’s vision as an original, unified perception.(8)

Victor Sloan has direct experience of the Northern Irish conflict. “His strength lies in his ability to transcend its local aspects by situating it within a universal theme: the interpenetration of the present by the past.”(9) While Jeff Wall, with his “Dead Troops Talk” image, is targeting Late-Capitalism, Victor Sloan with his allegorical “Borne Sulinowo” series, is again exploring the socio-political and cultural phenomena of

|

| Map, silver gelatin print, dyes, inks, bleach and gouache, 80cms x 111cms, 1995 |

Victor Sloan knows that is a long way from a ceasefire to peace. In the process towards a lasting peace demilitarisation is a necessary step. With his Polish Series, Sloan appears to anticipate the demilitarisation, and perhaps, even the withdrawal of the British Army from the six Counties. But, he is nonetheless cautious, if not sceptical, of the new political developments. Whatever happens, we will still need artists like Victor Sloan who work against the industrialisation of seeing, against the mechanization of sensuality.

Notes

(1) Heiner Müller, “Jenseits der Nation”, Berlin

(2) Neal Ascherson, “After the Freedom, Bread”, Independent on Sunday, 13 November 1994 , p. 23.

(3) Jean Baudrillard, “Transparenz des Bîsen”, Berlin

(4) see Paul Virilio, “Das Privileg des Auges”. In: Bildstorung. Edited by Jean Pierre Dubost, Leipzig

(5) see Victor Sloan ‘Walls’ catalogue, Orchard Gallery, Derry ,1989.

Brian McAvera, ‘Marking the North: the Work of Victor Sloan’, Dublin/York, Open Air,

Impressions, 1990.

(6) see Jeff Wall, “Dead Troops Talk”, catalogue, Luzern: Kunstmuseum,

(7) Terry Atkinson, “Dead Troops Talk, Jeff Wall, pp. 33-36.

(8) see Rosalind E. Krauss, The Optical Unconscious, Cambridge , Massachusetts London

(9) Brian McAvera, “Marking the North”, p. 11.

Extract from Beyond Borne Sulinowo by Jürgen Schneider in Victor Sloan: Borne Sulinowo, published by the Orchard Gallery,

Victor Sloan: Borne Sulinowo

by Dr Riann Coulter

In October 1992 a town appeared in north-west Poland. Borne Sulinowo, known in German as Gross Born, was absent from maps for almost fifty years. On 18 August 1938 Adolf Hitler had officially opened a German military base there. Seven years later the town, and the surrounding 180 square kilometres of forest, were taken over by the Soviet Army and erased from the official maps of Europe: a town housing 25,000 people hidden from the outside world.

Following the change of political regime in Poland in 1989, an agreement was reached to withdraw the occupying Soviet Army. The last of the large military units withdrew from Borne Sulinowo in October 1992, and the town was transferred to Polish rule. The transformation of Borne Sulinowo from a hidden Soviet military base to an abandoned Polish town was part of the wider withdrawal of the Soviet Army from Eastern Europe. This was the largest military operation since World War II, and a process hastened by the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9th November 1989, twenty-five years ago this month.

In the summers of 1993 and 1994, shortly after Eastern Europe began to open up to Western visitors, Irish artists were invited to Poland to participate in the Irish Days Festival. This event, organised by Wladyslaw Kazmierczak, Director of the Baltic Art Gallery in Ustka, Poland, celebrated Irish culture and gave Irish artists the opportunity to produce and exhibit work in the gallery and discuss their practice with Polish artists and curators. In 1994 Victor Sloan was one of thirteen Irish artists invited to participate.

The history of Borne Sulinowo, and its political significance, may not have been familiar to the Irish artists who travelled there during the summer of 1994. Sloan recalls an early-morning bus journey after a long night of Polish hospitality. Those who rose in time to join the expedition were not disappointed. For Sloan, this was a pivotal moment. What he discovered beyond the barbed wire, was a surreal hinterland where soldiers and their families had played out a myth of normality behind a veil of secrecy.

In the months since the Soviet Army had withdrawn, nature had begun to encroach and reclaim the streets. The surrounding forest appeared to be a rural idyll but, as Sloan discovered later, the whole area was heavily polluted and there was a persistent danger of encountering a mine or an unexploded bomb. The town was deserted apart from the police station and a small bar. The Soviet street names had been changed to patriotic Polish titles such as ‘Street of the Polish Army’, and scrap merchants were beginning to plunder anything of value.

Sloan was fascinated by what he saw and photographed the flotsam and jetsam that remained. The evidence suggested that the Soviets had left in a hurry. Food was left on kitchen tables and personal effects were abandoned. Sloan was particularly interested in the detritus that had been left behind. The photographs, propaganda posters, films, maps, books, ammunition and military badges: all abandoned evidence of what had once been a bustling, but isolated, way of life.

The indelible stain of the town’s recent history was evident not only in the chemicals and pollutants dumped there but also in the graves, both Soviet and Polish. Sloan’s camera recorded headstones with photographs of long-dead infants alongside military and religious symbols. In one image a religious statue watches over the untended graves. This Christian symbol, familiar in Poland, and Ireland, appears out of place here where the Soviet hammer and sickle officially reigned.

In an essay written in December 1994 Jürgen Schneider asked if the soldiers based in Borne Sulinowo were living as victors. Sloan’s bleak images suggest not. Damp and mould invaded the barracks before they were abandoned, and the need for secrecy imprisoned the soldiers and their families in the base. Russians were born and died in Borne Sulinowo and yet they were effectively itinerant people who had to abandon their homes at short notice. The historically strained relations between the Polish population and the Soviet army came to a head in 1990 when the Soviet Union finally admitted responsibility for the massacre of 45,000 Polish soldiers in 1943. For almost fifty years they had blamed the Nazis for the murders, particularly the mass grave at Katyn Forest where the bodies of 4000 Polish officers were discovered. Within this context, perhaps the secrecy that surrounded Borne Sulinowo was to protect the Soviet Forces rather than to control the Poles.

The images that Sloan produced when he returned from Poland are both extraordinary art works and a remarkable testament to a significant moment in recent European history. Although he took reels of documentary photographs in Borne Sulinowo, the resulting images are neither photographs nor accurate records of that encounter. Starting out as large photographic collages created using layered and manipulated images, each unique print was finished by hand. Laying the prints out in his back garden, Sloan worked on them with paint, toner and bleach until he was satisfied with the effect. The results are often surreal and always visually arresting. These are images which cannot be digested in a glance, and demand concentrated consideration.

In Statue a photo of the religious figure in the cemetery is inverted and semi-obscured by a mug shot of a soldier. Nature threatens to invade this hybrid image but is thwarted by the intense blue and sepia tones that dominate the series. Sepia suggests a bygone era, but the blue, reminiscent of the Russian military’s blue berets, stains like a radioactive dye, or the seepage of something toxic into the environment. In Slide a child’s toy and the faceless flats that housed families in Borne Sulinowo are framed by the dominating silhouette of a soldier whose features are hardly discernible. Mikhail Gorbachev is the leader in the art work of the same name. Has his face been ripped in anger or by accident? Brush strokes are visible, tinting his skin like a makeup artist preparing the leader for a press conference. The construction of history, especially, in an oppressive State, is made evident through the formal elements of these works.

In Map part of Europe has been violently torn from the whole. The image frames the reality of territorial division in this part of the world, where borders have changed with every regime and people have been displaced, resettled and displaced again within a generation. In Bars a training ground becomes a battle field. Blotches of bleach mark the rugged landscape in the foreground, suggesting bodies churned up by a post-war plough. At first glance the training bars of the title resemble the skeletons of burnt-out sheds. Elsewhere in Poland such sheds were the tools of Hitler’s final solution. Closer to home the marked landscape is reminiscent of the futile hunts through the bogs of Ireland for the bodies of the disappeared. The layered complexity of Bars, and other images in the series, permits the play of meaning. Despite their particular geography, the visual richness of these works prevents them from being confined to a particular place or time. Just as so much of Sloan’s work set in Northern Ireland, is, on closer examination, universal in its reach, so the Borne Sulinowo series reflects back onto Northern Irish history.

Writing about Sloan’s Northern Irish work in 1990, Brian McAvera observed, “His strength lies in his ability to transcend its local aspects by situating it within a universal theme: the interpenetration of the present by the past.” The Borne Sulinowo works are relevant within a Northern Irish context, particularly in terms of the Good Friday Agreement, which was signed in 1994, when Sloan was working on this series. In both Poland and Northern Ireland, the most challenging question is how “we cope with the toxic legacy of conflict, of unspeakable and horrible actions.” The Borne Sulinowo series is about aftermath, demilitarisation and departure. As Aidan Dunne has written,

“The deserted Borne Sulinowo is a striking example of a problematic social space, like other environments Sloan has sought out. While there is no overt connection with the North, Sloan’s work acts as a quizzical commentary on the role of the British Army in Northern Ireland and, more, given a persistently prescient streak in his work, on the question of what sort of place Northern Ireland might be after the conflict. His work on the Polish material was encouraged by the IRA’s ceasefire in 1994. The pictorial detritus of the abandoned army town strangely parallels and prefigures the troop withdrawals in Northern Ireland and the questions that came to the fore during the prolonged interrupted negotiations.”

It is also significant to consider how Sloan’s experiences of living through conflict in Northern Ireland frame his creation of politically charged work about another place. We take it for granted that Northern Irish artists can, and do, create political work, but as Jürgen Schneider recently observed, “‘political’ art is marginalised in Germany where everything is dominated by the art market.” Without a significant art market to cater to, Northern Irish artists, have the freedom to make political statements that others shy away from. More importantly, Sloan has spent decades developing the tools, techniques and sensitivity to tackle political subjects. He is equipped to engage with the issues that are raised by Borne Sulinowo’s particular history. He recognises this liminal landscape and is comfortable in this contested territory.

Dr Riann Coulter, Curator, F.E. McWilliam Gallery & Studio, Banbridge.

from Victor Sloan: Borne Sulinowo exhibition publication, The University Art Gallery, Belfast.

November 2014

1 – The other artists invited in 1994 were Cathy Wilkes, Brian Connolly, Sean Taylor, Alastair MacLennan, Maurice O’Connell, Sandra Johnson, Jim Buckley, Alice Maher, Eddie Stewart, Heather Allen, Pauline Cummins, John Kindness, Anne Tallentire and Jürgen Schneider.

2 – Jürgen Schneider, ‘Beyond Borne Sulinowo’, Victor Sloan: Borne Sulinowo (Derry, The Orchard Gallery) 1995, p. 5.

3 – Brian McAvera, ‘Marking the North: The Work of Victor Sloan’ (Dublin & York, Open Air Impressions) 1990, p.11.

4 – Aidan Dunne, ‘A Broken Surface: Victor Sloan’s Photographic Work’, Victor Sloan (Ormeau Baths Gallery/Orchard Gallery) 2001, p.116.

5 – Aidan Dunne, ‘A Broken Surface’, p.110.

6 – Jürgen Schneider email to the author, 21 November 2014.

Return to Works